Professors respond to digital distraction

By Leah Huyard – Horizon News & Feature Editor

Kendra Burkey’s speech class received a final warning last month: If they used their phone in class they would get half credit for the day. A similar policy is listed in her syllabus, but she hasn’t enforced it until now.

“You have to be present physically, mentally, and spiritually to be counted present,” she said.

Students may object to this strict policy, but for Burkey, professor of communication, and others, cell phone usage is getting out of hand.

“Distraction in the classroom has always been a problem, but digital distraction takes it to a whole new level,” Burkey said. “It’s never been so easy to be disengaged.”

Burkey isn’t the only faculty member on Hesston’s campus struggling with how to control the phone usage of students in the classroom. Many teachers believe cell phones hinder learning.

Some Hesston professors have found ways for students to use their phones in productive ways, such as for game clickers or as calculators. But more often, teachers say phones are used as devices of distraction. David LeVan, business, English and economics professor, has two other reasons why he does not allow students to have their cells phone on their person during class time.

One, research has shown that people have a very difficult time multitasking. LeVan says that responding to a text or looking a Facebook is distracting, and that it will have a negative impact on the student and the student’s understanding of the material. Two, LeVan finds it “personally insulting” when he’s trying to convey the material of the lesson as well as he can and students are not respecting him by listening.

“If something is really that important,” LeVan said, “students can certainly leave class and go do what they need to do.”

It’s also a pet peeve of LeVan’s, which then impacts his ability to teach students. He gets frustrated when he sees students not paying attention and in turn interferes with his instruction of the class.

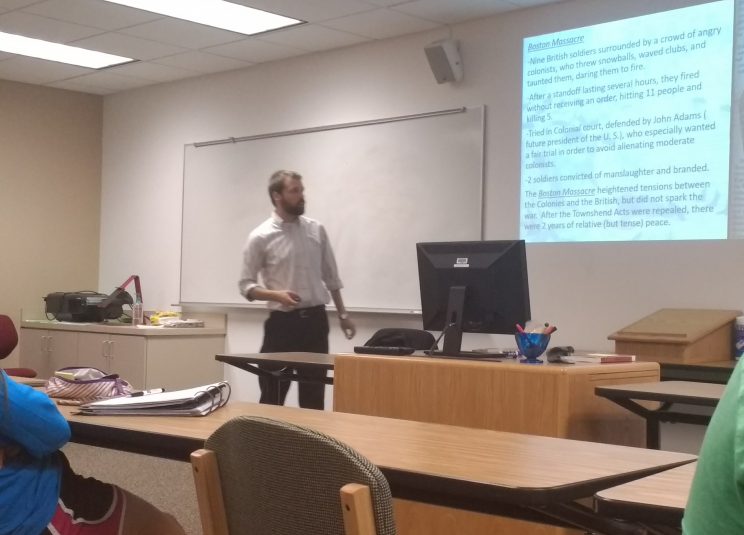

Other professors, like English and history professor Peter Lehman, have found that ignoring the phones works better for their classroom. Lehman says that he would rather keep teaching in front of the class than stop and ask the student to put their phone away.

“Just because I want to keep the flow of class moving, I don’t stop everytime I see a phone out,” Lehman said. “If they’re aren’t distracting other people, the class just moves forward, and I only address it when I need to.”

So should phone usage be left up to individual instructors? Or does Hesston need to start thinking about a campus wide phone policy plan? Burkey says she would like to see faculty members “have a united front.” She says one policy would communicate Hesston is committed to classroom engagement. LeVan and Lehman agree, but with reservations: It would be hard to enforce, and it would get in the way of the current emergency alert system that Hesston sends via text.

Whatever strategy professors use, the problem of distraction from cell phones remains. And it’s not just in the classroom. When students leave class, many pick up their phones right away and walk through campus, heads down, more intrigued by their social media than what’s around them.

“It would be wonderful,” LeVan says, “if we were able to walk the campus and smile and say hello to people over and over again, and engage in conversation, as opposed to dodging them as they’re not paying attention.”

Interested in what cell phone policies other Hesston professors have? Read from a variety of phone guidelines professors have in their classrooms.